EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first part of an essay written for The John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy, where it first appeared.

Read Part II here and Part III here.

Since at least the 1920s, America has done a fine job of nurturing its budding classical musicians within a large and well-funded network of conservatories that function either as independent institutions or else as colleges within larger universities. The grand venture of transplanting this pinnacle of European artistic achievement into the fertile soil of the New World has been, in this regard, a spectacular success. Whereas the American symphony orchestra, the anchor institution of its city’s cultural life, used to be filled necessarily with imported virtuosi from the old country, we have been, rather impressively, producing our own talent for the last century – and with plenty to spare. In fact, American musicians now frequently fill the ranks of orchestras around the world and represent some of history’s finest conductors and concert soloists – including, among others, Leonard Bernstein and Lorin Maazel, Yo-Yo Ma, Isaac Stern, Andre Watts, Lynn Harrell, Joshua Bell, Jessye Norman, Beverly Sills, and Leontine Price. Though they were educated here in America, these musicians not only met Europe’s highest standards, they have set new ones. And American composers such as Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, John Adams, Phillip Glass, and (again) Bernstein have created what we recognize today as the American sound – just as Sibelius did for Finland, Ravel did for France, Elgar for England, and Mozart for Austria before them. America, like a prosperous European outpost, has contributed mightily to the classical music canon and to the enterprise of institutional continuity for subsequent generations.

So can we say, then, that all is well in the world of higher music education on this side of the pond? Perhaps surprisingly, almost everyone you ask today will answer that question with a “no” – sometimes apologetic and conciliatory, other times resounding and emphatic. While we might easily dismiss the specious arguments they offer for that seemingly unanimous evaluation, we should see the underlying shift that their reasoning betrays as a cause for real alarm.

The loudest cries for reform seem always to come from that peculiar class, the professional critics – and from the precariously placed careerists who are charged with the unenviable task of answering them. Of course the easiest and most politic way to respond to criticism is to simply echo and affirm its loudest voices, and sometimes that is also the correct response. But that is to say that it is not always the correct one. Nevertheless, in an age increasingly intolerant of dissent, seduced by sophistry, and drunk on the heady politics of change, this is rapidly becoming the only acceptable response. Perhaps this is because, in trying to deflect criticism by repeating it, we inevitably add to our vigorous capitulation enough sanctimonious zeal to convince everyone that we too are playing for “the offense” rather than “the defense.” As the consensus and enthusiasm build in this way, to stand athwart the direction of their progress is to take a dangerously indefensible position and to confirm the insularity of which the institution is accused.

But if we suspected that at one time the cries for reform coming from within the academy were merely voices of apology and acquiescence, we should now acknowledge that they more often have the tenor of true revolutionary fervor. The noise continues to rise toward a fever pitch and we hear the same earnest chant from all sides, echoing as it does through the halls of academia, the vaulted spaces of our concert halls, and the vast virtual spaces of popular and professional media. It’s starting to sound like a self-evident truth: there is, indeed, something very wrong with the state of higher music education in this country.

Essentially, the voices all seem to be chanting that it’s not sufficient anymore for music schools to turn out graduates who are merely good or even exceptional classical musicians. That, we are assured, is not enough for an aspiring musician to get by on in the modern world. To be sure, it’s famously hard to make it as a musician. It requires a staggering commitment of time, discipline, and passion, after which there is no guarantee of a living. Full-time professional positions in classical music ensembles or institutions are few and very hard to come by. Competition is fierce. But so it has always been. There is nothing peculiarly “modern” about this fact. 1

What is modern, however, is both the idea that society owes us a living for being brave enough to “follow our dreams” and the wide-spread access we now have to higher education based solely on our predilections and our ability to pay for it. We are all raised now on the mantra that we can be anything we want to be when we grow up. Of course, it’s not true. That’s obvious when we’re talking about brain surgeons, rocket scientists, or even professional athletes. And we accept that. But it’s a touchy subject when we get to the arts – or anything that we long ago labeled as creative or purely subjective. We can’t see any objective reason why we shouldn’t be successful in a pursuit that depends only on our innate genius for creativity and our personal passion.

So, it seems, we are now holding our music schools accountable for our children’s failure to launch their dreams – based, presumably, on two more, recognizably modern themes: firstly, the belief that our educational institutions owe us, at least in part, that unalienable right to the pursuit of happiness which we seem to mistake as an entitlement rather than a freedom – as we are wont these days to do – to be whatever we want to be in life; and secondly, the tendency to see the student as a consumer and his education as a product, for the purchase of which he incurs, freely but perhaps unwisely, dangerous levels of debt. This last idea is coupled with the realization that the “product” may in the end prove to be of little or no quantifiably utilitarian value – a crime in itself in our modern age.

Calls for change, therefore, often begin by sounding like consumer advocacy. As one young blogger and self-described “musically inclined composer” – who has, incidentally, dedicated himself to the interests of the aspiring music student – puts it:

[I]t is without question the truest responsibility of music schools to prepare every single one of their student musicians for the real world of music. Why? I think [sic] two reasons – one, for the moral and ethical responsibility of a school to students who shell out over $200,000.00 or more for a four year education.

His phrasing is ubiquitous. Over and over again, we’re reminded of the need to equip students for the “real world” of music, or for the “realities of the modern world” – which, by the way, we’re all expected to agree has little or nothing to do with the world that came before it. And what follows inevitably is a flood of suggestions for the program of the revolution, each with varying hierarchies and degrees of absolutism. The College Music Society’s Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major (TFUMM), for instance, takes a particularly hard line and “believes that nothing short of rebuilding the conventional model from its foundations will suffice….”2 But whatever their aggressiveness, suggestions from all corners generally coalesce around a few identifiable themes that we’ll treat briefly in the installments that follow. Let’s call the first one Entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship

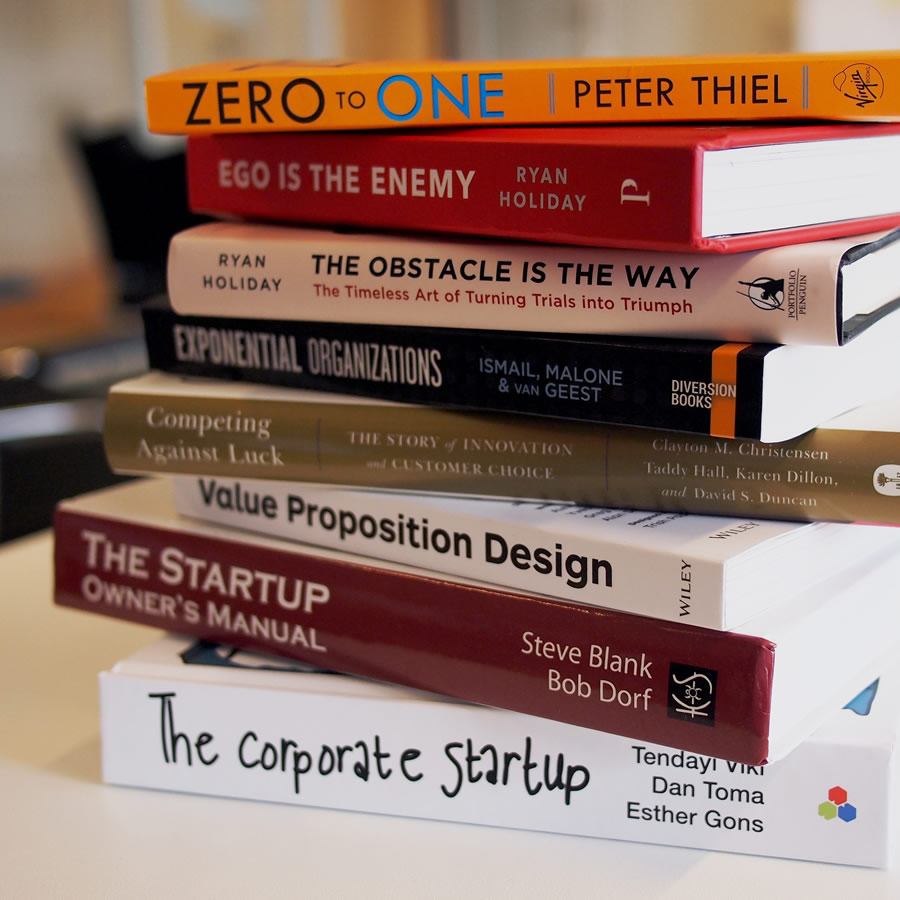

The world of higher music education reform is abuzz with the excitement and promise of entrepreneurship. And it’s equally agog over Claire Chase, the movement’s undisputed and enthusiastic poster child. After graduating from Oberlin Conservatory in 2001, Chase’s very visible involvement with the contemporary music scene earned her a MacArthur Genius Grant in 2012. Since then she’s become something of a fixture on the inspirational lecture circuit, delivering lauded convocations, speeches, and keynote addresses about entrepreneurship at universities, conservatories, festivals, and national meetings. Notably, she was the keynote speaker last year at the League of American Orchestra’s annual conference. So what does Chase have that everyone in the classical music world wants?

She has, more effectively than anyone else, made her watchwords those pointy and frenetic adjectives that we use to describe the nature of entrepreneurship – words like disruptive and innovative. And those are proper associations because they do describe the nature of entrepreneurship in the free market. They do not, however and most importantly, describe the process by which a tradition such as musicianship is handed down from one generation to another. In fact, they repudiate that process, which we might describe with words more like disciplined and imitative; and it’s not at all surprising that those who tout entrepreneurship in the musical academy in their next breath vehemently disavow the practice of “teaching as it was taught to me.”

There is no shortage of disciples willing and eager to compose odes to “musical entrepreneurship” or to the power and value of all things “disruptive.” Chase distinguishes herself by going farther and harder – by being more extreme and edgy – than the rest. For all that, she is something like the precocious toddler who has discovered that some charming little antic has earned her the approbation of the all the adults in the room and so repeats it with growing excess and exaggeration until it becomes a grotesque nuisance – certainly no longer amusing and maybe even dangerous. In a similar fashion, Chase has taken her repudiation so far that she has turned her disruptive “model” of entrepreneurship back upon itself.

The MacArthur Foundation honored her with its Genius Grant for “forging a new model for the commissioning, recording, and live performance of contemporary classical music.” 3 But in a talk entitled Debunking, Disrupting, & Rethinking Entrepreneurship, delivered last year at Northeastern University, Chase described her innovative model, referring to her contemporary music ensemble (ICE), in this way:

“The truth about the ICE model is that it isn’t a model…. It’s a way of making music that’s constantly changing.” The company cancels festivals when they begin attracting too many people and move [sic] on from ingenious initiatives when other organizations start replicating them. “We frequently destruct our own models,’’ Chase explained. “It’s difficult to get people to let go of something when it’s successful but we do it at ICE.” 4

The absurdity of that elitist hipster-ism cannot be lost on anyone living in the real world, operating in the free market, or with a family to support – and that, of course, is precisely who critics purport to be worried about when they argue that student musicians should develop entrepreneurial skills. The fact that Chase continues to be taken seriously as the savior of classical music by the academy is perhaps conclusive proof that it does not in fact exist in the real world. The fact that the League of American Orchestras gave her the podium – to say nothing of the prominence awarded her as the keynote speaker – at their last national conference should alarm anyone who recognizes that our orchestras should aspire to and crucially need to attain some continuous and dependable level of sustainability if they are to survive.

To be fair, most suggestions for the incorporation of entrepreneurship into programs of higher music education focus on more pragmatic approaches. They agree generally on the idea of adding business classes to the curriculum. We can hope, I’m sure, that in those classes students would learn how to construct – or at least how not to destruct – successful business models and might also acquire a smattering of other skills, such as the ability to write a business plan or to build a website and a handy proficiency at self-promotion. But to the extent that this strategy holds more promise, it is also more insidious.

We should remember that the whole point of this exercise is that the majority of students, who will not in the end find full-time professional positions, should learn thereby how to make for themselves some other kind of job and some other kind of living – just as musicians in all eras have had to hustle to make what was often an ad hoc living by performing, teaching, and recording wherever they could. Even if it is not a need peculiar to the modern world, it has the attractive gloss of being newly identified, and reformers have latched onto the potential of classes in entrepreneurship, technology, business, marketing, and self-promotion for student musicians. They are enchanted by the endless, magically profitable possibilities they plan to create for young conservatory graduates – who are bound to innovate something musically disruptive and revolutionary, or at least visionary and creative, if someone will just teach them to write a business plan or build a website.

No one, of course, argues with the fact that these business classes will inevitably displace some of the coursework that has been traditionally required as important for the development of the classical musician, but there is a flurry of debate over which of those requirements are irrelevant now that we live in “the modern world.” It should be obvious, however, that we’ll only make it more likely for our entrepreneurial students to find success as professional musicians if the requirements for professional musicianship really are in fact giving way in to skills like Tweeting and blundering through some rudimentary HTML. And perhaps they are – that’s something else for us to worry about. For now, however, I can confidently assert that these new skills won’t help young musicians to get or keep jobs in our nation’s orchestras. And more importantly, I’d argue that to claim that these are the skills that could or should make a professional musician successful – today or any other day – indicates a level of cynicism that’s inappropriate in those charged with training our nation’s future classical musicians.

Nevertheless, teachers and directors at progressive-minded music schools are piling on top of each other to get on the entrepreneurial bandwagon – throwing, if necessary, musicianship “of the past” beneath its churning wheels in order to get a better leg up. DePauw University proudly announces its shiny new program for music study with these words:

The 21st Century Musician Initiative is a complete re-imagining of the skills, tools and experiences necessary to create musicians of the future instead of the past – flexible, entrepreneurial musicians who find diverse musical venues and outlets in addition to traditional performance spaces, develop new audiences and utilize their music innovatively to impact and strengthen communities. 5

No doubt you noticed that surprising bit tacked on the end. This will bring us to our next major theme and the second part in this series.

Endnotes

1 We might even point out that today, on the whole, there are more professional institutions of classical music employing more musicians in more corners of the globe than there have been at any other point in the history of classical music.

2 Accessed 8/20/15: www.music.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1859.

3 Accessed 8/20/15: www.macfound.org/fellows/860/.

4 Accessed 8/23/15: www.northeastern.edu/news/2014/11/clairechase/.

5 Accessed 8/23/15: www.depauw.edu/music/21cm/.