EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an edited transcription of the address delivered by Richard Bogomolny at our inaugural The Future of the Symphony Conference in September 2014. View the video of this presentation in its entirety.

I just want to begin by saying what an honor it is to appear on this program with such highly credentialed speakers, and I don’t take this lightly. I’ve been asked to talk about how the Cleveland Orchestra operates, focusing more on the practical side. But along the way I have to tell you those things we believe in and those things we don’t.

My own personal history is that I grew up in the supermarket industry, and I retired from that business. I wouldn’t mention that except for Andy’s comments yesterday concerning potential problems when you bring too much business discipline into an arts organization and what the potential is for that, both good and bad. I’m glad I had the business experience to apply to it, but historically, when you become the president or chairman of this organization, you never lose sight of the fact that the art is the most important thing. Music is number one. We’d like to say that the musicians are number two and everything else is number three.

I grew up during the George Szell era. This was the era during which the orchestra became known far and wide for artistic excellence. There were two elements of pride for the community in those days. They were the Cleveland Orchestra and the Cleveland Browns – that’s where my head was when I was growing up. My mother studied at the Damrosch School in New York, which later became Juilliard, and my brother and I each studied music and grew up loving classical music. He played the clarinet and French horn and now plays classical guitar, and I the violin and viola. We both studied with prominent members of the Cleveland Orchestra and attended the national music camp at Interlochen for two summers. It was at Interlochen that I realized I was never going to be good enough to play at the level where I would like to play.

Similar Problems

Here is a kind of disclaimer: while I think the kinds of things that impact orchestras today are fairly common among the orchestras, the solutions, in my view, have to be local. What works in Cleveland may or may not work elsewhere, and there are reasons for that. So I’m not here to say what things other orchestras ought to be doing simply because we’re doing them – it’s not that at all. And we make as many mistakes as the next organization does. Cleveland itself is a major part of what and who we are. But I think we have four issues in common.

It’s fairly obvious that financial resources – or the lack thereof – are a major issue in the industry. The development of audiences – their age, their size, and their demographics – is another thing. That leads to the third problem, which is lack of true diversity on the stage, in the boardroom, and in the building. The fourth thing is that none of us suffers from a lack of qualified musicians. The world is continuing to produce more and better musicians than the major orchestras of the world can possibly support. Unfortunately, on the issue of diversity and inclusion, because of years and years of trying and failing, I don’t think that I have much that is useful to provide for you other than a long study of things that didn’t work. So I’m going to talk about history a little bit.

History

The orchestra was founded in 1918 by Adella Prentiss Hughes. She had two things in mind, both of which have remained central to our existence ever since. Firstly, she wanted Cleveland to have a great orchestra and to avoid the need of always having to import touring orchestras for classical music. And secondly, she hoped the orchestra’s musicians would form a cadre to teach in the Cleveland public school systems. And for most of this time, this has been true.

In 2018 we will celebrate our one hundredth anniversary. We are planning a celebration not of the orchestra but of our community, which has supported us for all of these years. In addition to the Orchestra, we run the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, and the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Chorus. We involve in these organizations as many people from northeastern Ohio, and some from even further away, as we can.

Severance Hall was opened in 1930. At the time it was called America’s most beautiful concert hall and I believe that it was. In 1956 or so, George Szell completely revamped and improved the acoustics by changing the concert stage and removing heavy carpeting and drapes, but in the process he buried the six-thousand-piece organ in the ceiling, making it impossible to play. This was at the beginning of the era of high fidelity, and Szell believed that we would be able to play the organ and broadcast it through very large speakers that were installed in the back wall, but that never happened.

Later, we revamped the whole Severance Hall again. We renovated it, we added to it, and we brought the organ down to the concert hall level, where it now stretches around three sides of the stage and is very playable. The hall seats two thousand people, all with an unobstructed view. And the acoustics are really quite good. I think the acoustics are one of the reasons for what is referred to as the ‘Cleveland Orchestra Sound.’ It’s a stage where the musicians hear each other better than anywhere else they’ve ever played.

In 1968 we opened our summer hall at the Blossom Music Center. It sits on 200 acres in the middle of the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. It was completely renovated in 2002, and the serious work of providing better accessibility, not just for the handicapped but also for the aging population, is being completed in phases over the next couple of years. The pavilion seats 5,700 and another 13,500 can sit on the lawn, all with good visibility. The stage is at the bottom of a natural bowl, with seating and access from the hillside. Touring soloists and guest conductors tell us that it’s the most beautiful and best acoustical outdoor classical venue in the world.

Franz Welser-Möst has been our music director since 2002. He is under contract through 2015 and we’re in the midst of negotiations to extend that now. He just recently resigned as the music director of the Vienna State Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic. I think he had the second longest tenure of anyone there, but when he took the job he said, “I’m not going to complete my term; nobody does.” And he didn’t.

The Cleveland Factor

I want to talk about the Cleveland marketplace. In 1955, we had one million residents residing inside of the city’s legal boundaries. Today we have 390,000. The city went from a manufacturing powerhouse for cars, steel, and oil refinement to a service economy where the largest current employer is the Cleveland Clinic. We were long ago a top-tier economy, and we became a second-tier economy in the 1970s and ’80s. By the recession of 2007–8, we’d become a third-tier economy. Last week the US Census Bureau released new numbers that give Cleveland the distinction of being the second poorest city in America. Detroit beat us out for the distinction of being the poorest.

But surprisingly, for all these years, the Cleveland Orchestra has been supported by our community as a top-tier orchestra with all the associated costs that go with it. We’re the smallest city in the world to have such an orchestra, and it would be easy to conclude that the people leaving Cleveland moved into the suburbs, but the numbers don’t really back that up. It means that our funding base has deteriorated and that support for all of our area nonprofits has fallen to fewer and fewer sources. Many of the area’s Fortune 500 companies have moved elsewhere or have merged – several major banks among them. In 2007, after a very large campaign, the city created a pool funded by a tax of thirty cents per pack of cigarettes for the use of the performing arts organizations in the area.

There’s one other factor besides the economics to be considered, and that’s the historical generosity of the community. In the words of Fiddler on the Roof, I’m speaking about Tradition. In Cleveland, the tradition of philanthropy has origins in the early 1900s with Andrew Carnegie, the Rockefellers, the Severances, and others. It has continued to this day, measured by what the Cleveland Orchestra raises, what United Way, Jewish Federation, Catholic Charities, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and a mass of others have raised annually. I believe that the United Way was originally the Community Chest and it was founded in Cleveland. And the Cleveland Foundation, which was the first community foundation in America, is currently the second wealthiest behind New York City. That’s all going on while people are leaving the area and the economy turns from heavy-duty manufacturing to mostly service and medicine.

But one of the things of interest is the fact that the Cleveland Orchestra had the highest market penetration for both ticket sales and per capita donations in the industry. No other orchestra has developed even half of what we have achieved in their marketplaces. Yet balancing the budget has always been a struggle. And here is why: the nature of the industry. My predecessor as president of the orchestra, Ward Smith, defined a nonprofit as the symphony orchestra. Why? Because the revenue earned from ticket sales and sponsorships never covered, even in the best of times, more than 47 or 48 percent of what it cost to operate. In recent times, that number has been closer to 40 percent than to 50. Covering the other 53 to 60 percent of the annual operating budget depends totally on fundraising – whether you called it endowment, annual bridge, special, or by any other name or combination of names.

On the business side of the symphony orchestra, I believe this is all one really needs to know in setting priorities. Next to governments, for which most boards easily possess the talent – whether they have the will is another story – fundraising is where it’s at in terms of financial success or failure. Every one of our trustees has a fundraising plan to which he has agreed and assists in solicitations for the annual fund drive.

There are some broad principles. It’s often suggested that if the board does the job of fundraising the musicians will be able to keep up with their compatriots in other cities in terms of pay, benefits, and retirement. Conversely, any lack of resources to pay for these increases is generally the board’s fault. And I believe that this argument may in fact be true in certain instances, but it certainly isn’t in every instance and it’s way too simplistic – it’s just not true in many cases, and in others it’s true only by degrees.

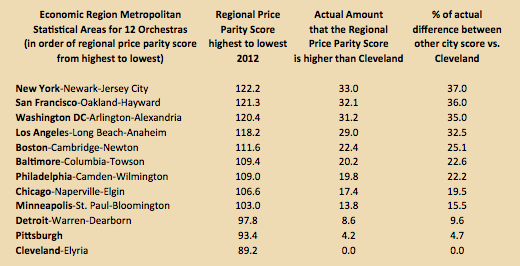

I created the chart in Figure 1 not with the purpose to compare orchestras, but to talk about marketplaces. There is new data released by the US Department of Commerce that measures what it really costs to live – not what the CPI is, but what it really costs to live – in each of the areas marked in the left-hand column. The ranking is the regional price parity score from highest to lowest. One hundred is the average, so for anything listed as above one hundred you can assume the cost of living is higher than zero. Those listed as the bottom three, all less than one hundred, are the more impoverished cities. You can say that it costs less to operate there. In the last column you’ll see the actual percentage difference between the scores of Cleveland and the other cities. Cleveland is listed at the bottom as zero; New York is 37 percent more costly, based on this federal study, than Cleveland; and Baltimore comes in somewhere in the middle at 22.6 percent more costly than Cleveland. There’s one other thing that you can deduce from this information. For a dollar spent in Cleveland, you’d have to spend $1.37 in New York to buy the same market basket; $1.19 in Chicago to buy the same thing; and, surprisingly for me, $1.22 in Baltimore. The purpose of the chart is just to show you generally the economics of the twelve major orchestras that I listed there.

What that means is that Cleveland was the eighth-highest paying orchestra in terms of actual dollars, but its musicians had more purchasing power than all the others because of the marketplace in Cleveland. As I said, one dollar spent in Cleveland would buy $1.37-worth of products in New York City. Based on purchasing power – which none of the union players wants to hear about and so, to that extent, what I’m talking about is highly sensitive – the Cleveland Orchestra musicians clearly are able to afford the nicest standard of living compared to the musicians in all the other cities we’ve looked at. And that is, unfortunately, because Cleveland is one of the poorest areas.

But we also adhere to a legal principle: to agree to pay more money than what the figures tell you will be available – as many orchestras have tried to do over the years – is a breach of our fiduciary responsibility to the organization and to the community. And that’s how a lot of orchestras have got themselves into deep trouble, betting on the if-come, which in fact rarely does come.

Musicians like to look at how they stack up against their peers in terms of base pay as a pure number. I think this is certainly a psychological issue; it’s a feel-good issue. They want to be paid as well as Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, and New York, and the reason for that is the fact that they can, in many cases, logically say that they play as well. I would argue that these other things show much more than the relative base pay. But none of these arguments are the real reason for showing you these numbers. That, I will discuss in a couple of minutes. I just want you to keep in mind the background of these numbers.

What We Believe In

This is based on both personal and institutional experience. Let’s begin with Excellence. We believe that everything we do – every plan we form, every expenditure that we make – must be tested against what that action will do for or against the standard of musical excellence that we have followed for decades. In times of financial difficulty, only those activities not related to what we call being a world-class orchestra may be cut without consent of the board.

The other thing we believe in is the fact that it’s very hard to play an instrument at the level of the members of our orchestra, how very good the musicians have to be in order to get in in the first place, and how hard they must work in order to stay at that level and to uphold our artistic traditions. While growing up, many of these musicians were thought of as child prodigies in their own communities. It’s been my objective over the years to make sure that the trustees understand and believe that our musicians are special and that they, collectively, are the reason we’re in business.

We also believe that classical music is not dead, nor will the ability to hear any amount of music free on the Internet bury us. Our unwavering belief is that the live concert experience, with the audience being emotionally involved and connected to music, is enduring. You can ask our musicians and you’ll find that none of them buy into the proposition that classical music is dead. In fact, they’ve been asked that question by the Cleveland Plain Dealer, which for the last few weeks has been doing vignettes on each of the members of the orchestra, and one of the questions they ask is about the death of classical music.

Last summer we set attendance records at the Blossom Music Center for most attendees, highest average attendance per concert, highest number of age 25-and-under attendees, and the highest revenue – even with ages 18-and-under being admitted free with an adult ticket buyer. And we achieved this in two fewer concerts than we had the year before. Some of this is programming – and some is weather and that’s accidental – but it’s nonetheless true that what we’re doing is not dying.

We believe that we are the most efficiently run of the major orchestras, based on statistical comparisons of operating size and budget – currently around $50 million – and considering the fact that we operate both Severance Hall and the Blossom Music Center. Very few orchestras own and run their own venues. The trustees understand that, operating as tightly as we do, it is no longer possible to save the orchestra from a financial crisis by significantly cutting overhead. That’s already been done and we don’t permit mission creep in this area. We recognize that investments, by definition, must often be made in advance of actually achieving desired results. We also understand that some initiatives will fail or be far less than hoped for.

We believe that it’s neither possible nor desirable to save money by trying to balance the budget on the backs of the musicians. In a crisis caused by events outside our control, we do expect them to participate in sharing the sacrifice, and they have done so in the form of freezes, slower increases, and extra services – within the whole organization, including the music director, the executive director, and the senior staff. It’s very interesting that when Franz Welser-Möst took the podium to be our music director in 2002, we were getting right into the first recession of the decade, and he volunteered 10 percent of his total compensation before he had even conducted his first concert.

We do believe that musicians and staff need to be fairly paid, recognizing and taking into consideration their highly developed talents and level of skill. Here is the reason for the chart introduced earlier showing the relative economies of the twelve orchestras. I know that what I say next is controversial, but I believe it to be true nonetheless. We believe that our employees’ pay and benefits need to be negotiated based on the situation in the Greater Cleveland marketplace, not on what’s going on in New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago. Why? Because there is a fundraising reality. As I told you earlier, we’re always having to raise between 50 and 60 percent of our operating budget one way or another, and it’s Cleveland where we raise our money. It’s Cleveland where we do business, where we sell tickets; and it’s not possible to separate these functions from the Cleveland marketplace. The economies of other cities are not relevant to our ability to cover expenses in Cleveland. We cannot raise funds based on population numbers or the strengths of Boston or New York’s economies. And, as you can see, we have no ability to influence the buying power in these other areas. It’s often been proposed that we won’t be able to hire and keep the musicians unless we pay competitively, based on what the other major orchestras pay. For many decades we followed this path. This may or may not become a problem in the future, but as of now it isn’t and it hasn’t been. It’s currently a specious argument. It looks okay on the surface but fails in real life.

We believe that the number of musicians in orchestras must be set by the music director, not by economic issues – even though each open position can easily save more than $150,000 annually. In the early years we might have talked about this kind of thing, but I believe today’s board would not even hold a discussion on the subject. We understand that, even though we’re likely to have 250 musicians from around the world wanting to audition for a single open position, reducing the actual numbers of musicians in the orchestra, forgetting what the impact might be on sound balances, is a very slippery slope towards disaster. During contract negotiations, if there were a showdown on an impasse, we and the musicians all know that we could easily hire a whole new orchestra and replace the musicians with other talented musicians, but it would never again be the Cleveland Orchestra, where we have a tradition of hiring the best players who audition. And those players are then taken under the wings not only of the music director but also of the current members of the orchestra, who help teach them the style in which the orchestra plays Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, or Brahms. This remains a part of the George Szell tradition, and it’s been self-perpetuating. It’s kind of amazing to watch.

The orchestra does not like to go on stage unprepared – for either educational concerts or regular concerts. The musicians expect to work hard during rehearsals. They are skeptical if they don’t. They do not appreciate guest conductors who are so impressed or so overwhelmed that they coast in rehearsals. They complain to management not for being overworked but for not having enough rehearsal time. On tours, if you’ll walk the halls of the hotels as I’ve done many times, you’ll hear them practicing in their rooms instead of sightseeing. This is an experience that I’ve had many times, not just once or twice.

Every orchestra I know describes itself in terms of excellence – a term that is almost completely subjective and quite un-measurable. What is clear to me is that most orchestras in the top ten or fifteen largest American cities are very, very good. Why? Because their musicians are highly trained, highly skilled, highly dedicated, and substantial members of their local communities. They care about their job, their artistry, and their audiences. The orchestras themselves have usually good to great artistic leadership. Any one of these orchestras is capable of giving great concerts.

However, to my chagrin and the chagrin of others, playing great music and wonderful concerts ceased years ago to ensure the success of major orchestras. While that should be enough, the fact is that it isn’t and it hasn’t been for a while. This has certainly been the case in Cleveland. If it were enough, there would be no need for conferences like this one, the Philadelphia Orchestra would not have gone into bankruptcy, and the Detroit and Minnesota orchestras would not have had financial troubles. All of them play very well. On the flip side, though, I’m convinced that not playing great concerts of great music will ultimately ensure failure.

During both the recessions of 2001 and 2007–9, many of the things that hurt were predictable, even if out of our control. The endowment and pension funds got blasted by the market decline, creating unfunded liabilities in the pension fund that would require large cash payments over years to fix. Even if the market were to bounce back hugely, money in the endowment would never be able to ride the market back up because all of us were using principle to fund the operations. The donor base at all levels of wealth dried up because people were scared and their advisers were telling them to perhaps pay off their existing pledges, but certainly not to get any more heavily involved.

If you were like us, something else happened that I’ve never heard mentioned anywhere else in the industry. Each orchestra went into survival mode with key members of staff and board leadership involved day and night in trying to save the institution rather than in building the artistic side of the business, which is where our organizational leadership ought to be spending its time. In my view, there is only one way to avoid that trap, and that is to build a large enough endowment – roughly six times the annual budget – which can help an organization ride through inevitable business cycles. We’ve been trying to do this, with our goal to be there by our centennial in 2018. As of now, we’re not on track to do it but we may end up close.

This experience told us, though, that we really had to change. The change would likely have to be transformative rather than incremental. We had to look at things differently in order to do things differently. The Committee on the Future of the Cleveland Orchestra was formed and met for a solid year. It was made up of trustees, senior staff, and non-trustees who were important in the community, including elected officials and business leaders. They looked at every line of the financial statement and thought through every idea, crazy or not. It was during this time that we considered downsizing.

Because of the extreme hits to the market value of both the endowment and the pension plan and the resulting implications, we seriously looked at downsizing from a world-class orchestra to a truly regional orchestra. This was precipitated by potential large future operating losses based on loss of attendance and donors. Even though we already had the smallest operating budget of the other big ten orchestras except for Washington, we found that we could save millions of dollars annually by eliminating those costs which were directly attributed to being what we called “world-class” – that was union contract and benefits, touring, publicity, and so on. But there wasn’t one person in that room willing to propose such a step.

Since fundraising was crucial to any plan, we went out and spoke to our major donors, corporations, and foundations – particularly to our most generous individual donors, myself included. We asked them directly if we could count on their continued financial support for the downsizing plan to become a regional orchestra. The results were unanimous: nobody would give us the same amount or anything close to it for a lesser orchestra. Most wouldn’t contribute anything at all. We were built on excellence and that’s what we needed to be. Even when faced with the choice of going out of business versus survival by downsizing, the results were clear.

Strategic Imperatives

The turn-around plan was a five-year plan. Most of us had been operating traditionally with five-year plans and we were caught in that trap in those days. We looked at strategic imperatives, the excellence of the brand, and this might have been hubris but we believed, based on what others were telling us and what we saw ourselves, that we had established a kind of brand recognition that, if marketed correctly, could help us to develop residencies. The term “The Cleveland,” as we were known in Europe and Asia, often results in the need to answer the question, What is a Cleveland? But the last time we were in Japan, for example, the emperor and empress came to one of our concerts – something that no one at the hall could remember ever happening before. This evoked a huge response, with the audience standing and applauding loudly with much pride.

Well, the obvious part of the turnaround plan was that we cut nonessential overhead and reassigned work. We cut non-musicians’ labor with one-time reductions of five percent; music directors took another ten percent cut; the senior staff, including the executive director, actually voted themselves a ten percent reduction. The not-so-obvious idea was that of having to pursue excellence and innovation.

The goal was to remove six to eight weeks of total overhead from the Cleveland operating statement. This was based on the underlying reality that the economy of northeastern Ohio was too weak to support us as they had done in the past. We would have to look elsewhere in order to solve our financial problems. The target was to replace the lost ticket sales in Cleveland with ticket sales and donated funds from residencies outside the area. We would either strike out in a new direction with high risk or wait until the problem of our market ran us out of business. Even so, such a plan would take years to develop. We would no longer tour in a situation where Cleveland donors had to pay for the cost of the tours. We had to create a plan where, if we toured, the tours had to pay for themselves. Otherwise, we couldn’t afford to go. We defined residencies as a creative way to enhance the program of playing great concerts.

Miami would be our first opportunity because they were nearing the completion of both the new concert hall and the opera house and because of friends in their marketplace willing to help us. Miami’s hall was scheduled to open in 2006–7. We began negotiations and flew important individuals from Miami to Cleveland on multiple occasions so they could see what we were doing in our own marketplace, hear concerts and operas, and see initiatives in education at all levels. We reached an agreement to have the Cleveland Orchestra be the Orchestra in Residence at the Knight Concert Hall when it opened. The plan worked and the residency commenced in 2007. We started spending two weeks each season in Miami, then three weeks, and currently we’re spending four weeks in Miami, beginning in January and concluding in March of each year.

The activities in which the orchestra and musicians participate there are constantly evolving and expanding. Residencies require the building of strong relationships with existing organizations in the community – with schools and universities, cultural and education groups. First we were going to play two concerts each week at the Knight Concert Hall. The music and guest artists target the broad population of ethnic groups residing in Miami. The repertoire is often different from what is performed in Cleveland. We do side-by-side rehearsals and training sessions for musicians wanting to play in orchestras. We do that with the New World Symphony and with the Frost School of Music orchestra at the University of Miami. Our musicians and Franz Welser-Möst lead master classes and conducting sessions. We do chamber music, concerts and coaching, children’s concerts, family concerts, Musical Rainbows, and everything else we know to expand the geography beyond the Adrienne Arsht Center and the Knight Concert Hall. In some cases, in order to raise funds not covered by earned income from the sale of tickets, we set up and operate fundraising departments in residency areas. In Miami we set up the Musical Arts Association of Miami to fundraise. Every year Franz Welser-Möst opens the season down there, and we now have Giancarlo Guerrero as our principal guest conductor. He’s also the conductor of the Nashville Symphony.

Setting up residency is a huge investment in time and money, which are in particularly short supply during a recession. Currently we’ve established residencies in Miami, at the Musikverein in Vienna, the Salzburg Festival, the Lucerne Festival, the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, and the Lincoln Center Festival. Some of these we do in alternate years. We expect that a major new residency in Europe is likely to be announced shortly. We have established a brand. The marketplace sees that we know how to operate with flexibility during these residencies, to give value for the money and for the people we attract. We’ve not yet solved the problem, which is serious, of having our musicians away from home during residencies. In the case of Miami, it’s a four-week period, and it’s a difficult situation for all concerned. I’m not sure we’ll be able to solve it in the near term, but we’re all working on it.

One of our imperatives is what we call ‘Communicate and Align.’ Its intent is to have musicians, trustees, staff, and audiences engage with each other in new ways with no agenda other than getting to know each other on a different level. The musicians show up and socialize after ‘Fridays@Seven’ concerts, during which we host world music presentation parties. On another occasion, the Development department and the Fundraising committee of the board hosted a thank you lunch for members of the orchestra, most of whom came from rehearsal and stayed for two hours. We now have members of the orchestra on certain board committees, like the Total Concert Experience task force, the Fundraising committee, the Facilities committee, and the Technology task force. They have become valuable, contributing members. One string bass player, Henry Peyrebrunne, asked for and received a year’s sabbatical from Franz to work in our Development department and learn what fundraising is all about. He has recently completed that year and has joined the staff part time while going back to playing in the orchestra full time. There are many examples of dinners and after-concert events, open rehearsals, and such where we try to get the four constituencies together.

Just before the recession of 2007–8 hit, which closely followed the one in early 2000, we solicited a grant of $20 million from the Maltz Family Foundation to fund audience-building initiatives. After the recession hit, they honored the gift but spread it out over several years. With these funds we created the Center for Future Audiences. It had several goals, made all the more necessary by the second economic crash in the decade. We needed to rebuild our audiences and also to admit that lost subscription sales would be hard or impossible to rebuild. We would be fighting a universal, nationwide downward trend in subscription sales. We needed to concentrate on individual concert ticket sales and marketing. We needed to identify once and for all the existing impediments to concert-going and to set about removing them – things like the presumed dress code and concert etiquette. Does it really matter and to whom? There were winter and summer transportation issues. We targeted ticket packages that included busing from the various neighborhoods for our older population, particularly in winter, and out to Blossom, which is geographically halfway between Cleveland and Akron.

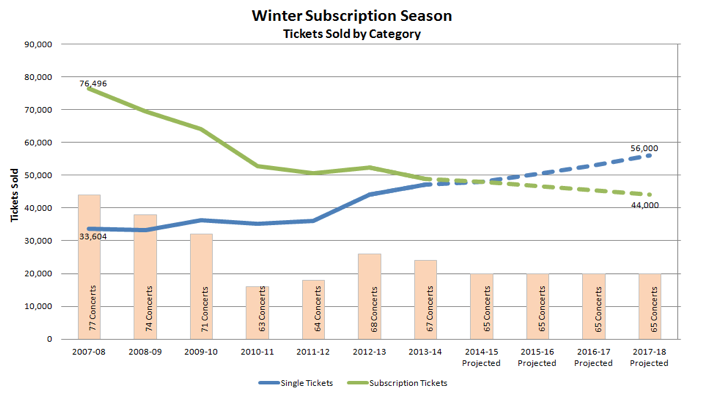

We needed to look at supply and demand, also. In terms of the numbers of concerts being presented and the demand for tickets created by current audiences, there were huge differences in the way we were operating now and the way we operated in the nineties, when the number of concerts was expanded because demand was high and good seats were simply unavailable. After 2001, we believed it was important to reduce the number or concerts and the corresponding number of available tickets. Really, the strategy was to set up a shortage of tickets, if possible, and increase the demand.

The chart in Figure 2 shows the number of subscription tickets – it’s the top green line that becomes dotted and trends downward – and it crosses the blue line, which represents individual ticket sales. Much of the overall ticket sales figures are the same. But what’s happening is that, with the demise of subscription purchases, many people are buying fewer concerts and so it takes more people to buy the same number of seats. That’s pretty obvious. What’s really happening is that we’re selling more tickets to more households today than in any other time in our history, but they’re buying fewer tickets because they’re not subscribing to multiple concerts.

We did a considerable amount of research on the question of ticket prices, which had gone up industry-wide at a rate twice that of inflation. There was a price-value reorientation that we thought was different, and we looked at the strategy by audience segments: 25 and under, 25 to 40, 40 to 60, and above 60. We found little or no resistance to the cost of box seats or the dress circle seats, always in big demand, with few seats available. We did find price concerns for most of the other audience groups.

We had tried many programs in the past to bring in younger audiences, particularly college students, but with little luck, even though Severance Hall sat in the middle of the Case Western Reserve University campus. The Maltz Family and the new grant were tied to this effort at every step of the way. First, we created a multimarket ticketing plan, dedicated to building the youngest audience in America by 2018, our centennial year. We tested an under-18-free flagship program at Blossom, and a year later we brought the under-18-free program to Severance Hall. With each free ticket there needed to be an adult ticket purchased. We created a student advantage pricing program for college students and a fan card program where $50 buys the student unlimited concerts, based only on the availability of tickets. We introduced the ‘Fridays@Seven’ concept, in which the orchestra plays probably two-thirds of its regular program of Thursday and Saturday that week, but with no intermission. Afterward there is a world music festival with food and a party in the Grand Foyer. And it was hugely successful! Last year we created the Total Concert Experience task force and populated it with people from all over the community to give us a fresh look at how to do things better.

The 25-and-under program has been hugely successful. All of the programs I mentioned earlier have helped, but the student program attracted 110,000 students since its inception – 40,000 during last winter’s season alone, which means that last season 20 percent of the Severance Hall audience was made up of people age 25 and under. Saturday night has become date night again, and we had twenty-three sellouts on Saturday nights during the season.

The backbone of success has been our focus on social media and the Web. In raw numbers, we went from attracting 13,000 hits in 2012 to over 100,000 last year. Most importantly, we focused on engagement, which is the number of people who actually participate once they get to the social media interface, and we found that ours is an industry-high at 17 percent.

We know we haven’t reached our full potential, but we also know the results have been very positive. In Cleveland, this means pursuing innovation with staged or semi-staged operas. Last season we created a fully staged production of The Cunning Little Vixen by Jánaček. We do ballet partnerships with the Joffrey and Miami ballet. We do a couple of concerts each year using the original music to movie scores for ‘Fridays@Seven’ programs, and we have adjusted the way we concertize around the world, only going where we cover our costs. And, as I said, where we have residencies, we don’t just drop in and play concerts; we do master classes, we do chamber music coaching; we spend a very intensive period of time – a week to two weeks at a clip – making very intensive use of the musicians.

We have residencies at home, where we go into particular neighborhoods and for a week play concerts in venues there – it could be a barber shop, a small café, or a supermarket. We play concerts in those, and at the end of the week it all culminates in a full Cleveland Orchestra concert at one of the big venues in that area, maybe a church or a school auditorium. Three or four months before the residency week begins, we go into the school system and we have over forty visits to each of the schools by our musicians. There they do what they do best in terms of trying to turn on the students to the kind of music that we play. For some of the younger students, this may mean showing them how to play the instrument, letting them touch it or hold it, and playing it for them. Attention span is relatively low, so we’re in half-hour segments there. But for older students, usually we plan an hour with a theme. And in the themes we select, we try to relate the music to the classes they’re being taught. Music becomes a way to teach those classes.

We do that because we learned over time that the first place a school system goes to get rid of budget costs is to the music program. And that’s because it’s usually a distinct program – they know how many teachers they have, they know how many dollars are budgeted, they know what getting rid of it all saves. We’ve taken a different tack, which is that when we go into the schools we try to teach the curriculum using music as examples. And we’ve had a great deal of success with that, but, as you can imagine, it’s very intensive. There are some orchestral musicians who have been doing this now for close to fifteen years and are really good at it. There are some musicians who don’t do it, but we’ve never had a shortage of musicians to go in and work this way in the schools.

To diverge, we played an orchestra concert under Franz at, I think, Saint John High School in Cleveland – an inner-city school. There was no music in the school at all. The principal tried to get the audience to order – we were all in the gymnasium – and he could not do it. I said to our orchestra’s president at the time, who was sitting next to me, “This isn’t going to go well.” We were scheduled to perform Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and that was the whole program. But the school’s principal couldn’t get the students to quiet down.

The minute Franz took the podium, without turning to his audience and without saying a word to them, he just started to play. He played the beginning, cut us off, and then started to speak. You could hear a pin drop for the rest of the hour. These kids – most of them were black and all from the inner city – came up afterward wanting different things: they wanted to talk, wanted autographs, wanted to know how certain things worked or didn’t. It took us three hours to get back on our buses to Severance Hall. I had thought, “We’ve got an uneducated audience and this isn’t going to go well.” But the reverse was true. They were fascinated by the music, by the rhythms. There was no hint of disinterest or boredom. It was amazing to watch.

Communicate and Align

Well, I could talk for hours on this subject, but the only other thing I will say has to do with board leadership. It’s my view that boards matter. It’s my view that board leadership is necessary for both artistic and financial success. These things need to be board-driven. And to my view, failures and successes, by whatever definition you use, ultimately fall to the trustees. It’s our collective responsibility to fix things and to see that things work.

In the nonprofit world, I think everybody will agree that decisions have to be made more by consensus than in the corporate world, where the CEO can just make a decision and edict that it happen. You can’t really do that with volunteers because the volunteers can leave at any time. And for the most part they didn’t bargain for problems. They don’t like to find themselves in the newspapers – they don’t want the institution involved in publicity they consider inappropriate. And if and when they do, they can walk.

You have to engage the board in a way that it’s willing to make the decisions, and the only way that works is by constant involvement. We have a rule at Cleveland that we never vote on a major issue the first time it’s presented. By the time it’s presented the first time, it will have worked its way through several committees, depending on the subject matter. The only exception is if something has a time limit imposed from outside the orchestra so that we have to vote on it at a particular meeting. But they get a chance to make the tough decisions, and for the most part we’re able to give them the decisions to work on when it’s still timely.

So things have worked for us in that way. It’s not that we don’t have the same kind of problems you find elsewhere. We are as bound to the community and its financial structure as any institution could be. It’s why I like to make the point that says that when you arrive at a contract, whether it’s for labor or for buying lights or music stands, it’s the market in Cleveland that matters and it’s there that we have to convince our musicians that they are better than fairly paid. But they have to consider the purchasing power of the community when they make that decision.