EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is part of our London Symposium: The Prospects and Promise of a New Hall for the London Symphony Orchestra.

As an erstwhile resident of London and attendant of innumerable classical concerts, it is not the ravishing beauty of the music but the ghastliness of the Southbank and Barbican concert halls and surroundings which leaves the most enduring, albeit painful, imprint on my mind. What the urbane theater and opera life so successfully achieves in Covent Garden is hopelessly lacking in these desolate music venues. Along with countless music-lovers and performers I have wished that those buildings would disappear forever from the face of London and the music world. The tabula rasa mentality that bestowed on us those loathsome aliens should at long last be turned against its coarse products in an overdue act of redemption.

And yet, judging from the glitzy brochure “Towards a World-Class Center for Music” – with foreword by the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Mayor of London – an aesthetically dumb kultural nomenklatura have not finished tormenting the good citizenry with conceptual incubi. How else could the Museum of London site and the Barbican environs be considered, even for an instant, as possible locations to re-found London’s classical music life? For all its political correctness and digital newspeak, the recent initiative proposes but a repetition of the errors that landed London with the unfortunate Southbank and Barbican complexes.

If it wasn’t for the gruesome architecture, the Waterloo bridgehead and Southbank site would be superb urban locations, rivalling the Piazza San Marco in Venice and Charles Bridge in Prague. However, while the redevelopment of the sinister music and theater buildings is a liberating prospect, it is yet unthinkable for political and cultural leaders. The partisan project of listing as historical the widely un-loved buildings has instead degraded the very notion of historic and cultural heritage. Why preserve what is not worth preserving?

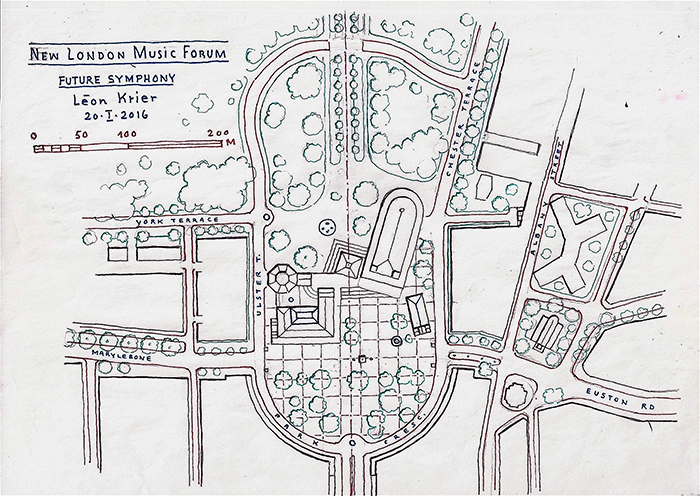

2016.” width=”700″ height=”496″> London Music Forum, conceived and drawn by Léon Krier, copyright 2016.

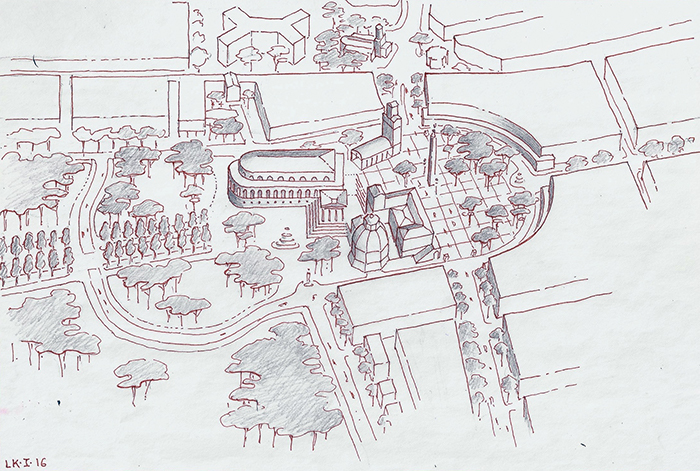

2016.” width=”700″ height=”496″> London Music Forum, conceived and drawn by Léon Krier, copyright 2016.

Meanwhile there is a choice location for London’s unrivalled musical offerings that, as far as I know, is yet unconsidered – namely, Park Square and Crescent. The fenced private reserve between Great Portland Place and Regent’s Park is served by two Underground stations and traversed by the major Marylebone/Euston Road axis. John Nash’s laconic and elegant crescent buildings make a quiet urban backdrop for a grand architectural “cymbal stroke” to resonate around London and the musical world: The London Music Forum, an inviting campus for everyone. Here, in the green “vestibule” of Regents Park, in proximity to the Royal Academy of Music, a new concert hall, a chamber music hall, a state of the art educational facility, practice rooms, restaurants and exhibition galleries can form a new urban ensemble that includes the complementary amenities required for successfully supporting the London Symphony Orchestra’s mission.

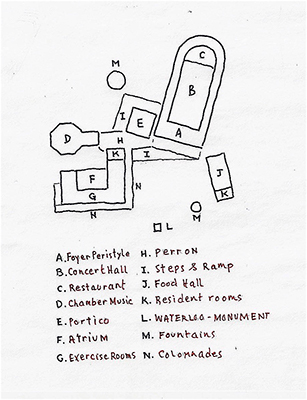

The main entrance and foyer, completely surrounding as a glazed-in arcade the concert hall itself, sit on a piano nobile dominating the new urban square to the south and Regents Park to the north and accessed by wide ramps and stairways through a monumental freestanding portico.

The concert hall replicates the Vienna Musikverein and Amsterdam Concertgebouw halls in size and proportions, while properly befitting the storied London Symphony Orchestra (LSO). The architecture of the new forum’s buildings and paving should speak the elemental classical language with which John Nash so brilliantly set the stage in character and color. Any required 21st century technology can be elegantly embedded in the design.

The new Waterloo monument and fountain, the monumental portico and the campanile are placed in the foci of the major vistas, Portland Place, Marylebone and Euston Roads, and Regent’s Park York Terrace, Broadwalk and Chester Terrace, all converging in this landmarked location. The entire space between the Nash Terraces and the music buildings is uniformly paved across Marylebone/Euston Road and shaded by the preserved venerable “Waterloo trees”.

2016.” width=”307″ height=”400″> London Music Forum, conceived and drawn by Léon Krier, copyright 2016.

2016.” width=”307″ height=”400″> London Music Forum, conceived and drawn by Léon Krier, copyright 2016.The colonnades along Park Crescent will soon animate with elegant cafés and restaurants an extraordinary new civic space, that anchors at long last, London’s musical life in a sophisticated urban setting.

Astute observers will notice that this very specific vision represents a departure from the orthodoxies that have lately governed civic and urban development – and that left their indelible scars upon the face of London in both the Barbican and Southbank. While the machinery of mega-project planning is already underway to impose on Londoners yet another soul-crushing, inhumane super-structure, it would be prudent to take a step back and consider just what were the mistakes of the halls we now need to replace, what should be done differently this time, and what are the priorities that follow from a broader, long-range goal of making a truly accessible and enduring home for the London Symphony.